Early Clarksville

The Woodlawn Plantation was owned by former Texas Governor Elisha Pease and his wife Lucadia. The couple’s stately home still stands at the corner of Pease and Niles Roads and is commonly referred to as the Pease Mansion.

Although Elisha and Lucadia were abolitionists from Connecticut, they were slave owners. According to oral history the quarters for the slaves who worked at Woodlawn were located somewhere in the area now known as Clarksville. In 1865 after emancipation, some of the couple’s former slaves remained in the Clarksville area and continued to work for Lucadia and Elisha.

In 1871, Charles Clark, a formerly enslaved man from Mississippi who had been living in Travis County, purchased two acres of land from Nathan Shelley, a former Confederate general. Clark built a home for himself on the north side of what is now the 1600 block of West 10th Street and sold the rest of his acreage to other freedmen. This area formed the nucleus of the freedom colony of Clarksville, which according to tradition, Clark envisioned as a place where former slaves could reunite with their families and friends, direct their own lives and freely practice their religion. Clarksville was one of the early freedom colonies established west of the Mississippi.

Early Clarksville was a densely wooded area located west of Austin, far outside of town. Out of necessity, it was a tight-knit, highly self-sufficient community. Residents built very simple wood-frame homes much like the Haskell House, hunted in the area, fished in the Colorado River, grew vegetables, kept cows for fresh milk, and raised hogs and chickens. They also hauled water from the river in ox-driven carts and caught drinking water in barrels and cisterns. For entertainment there were quilting bees, baseball games, picnics, candy-pulling parties and an annual Juneteenth parade.

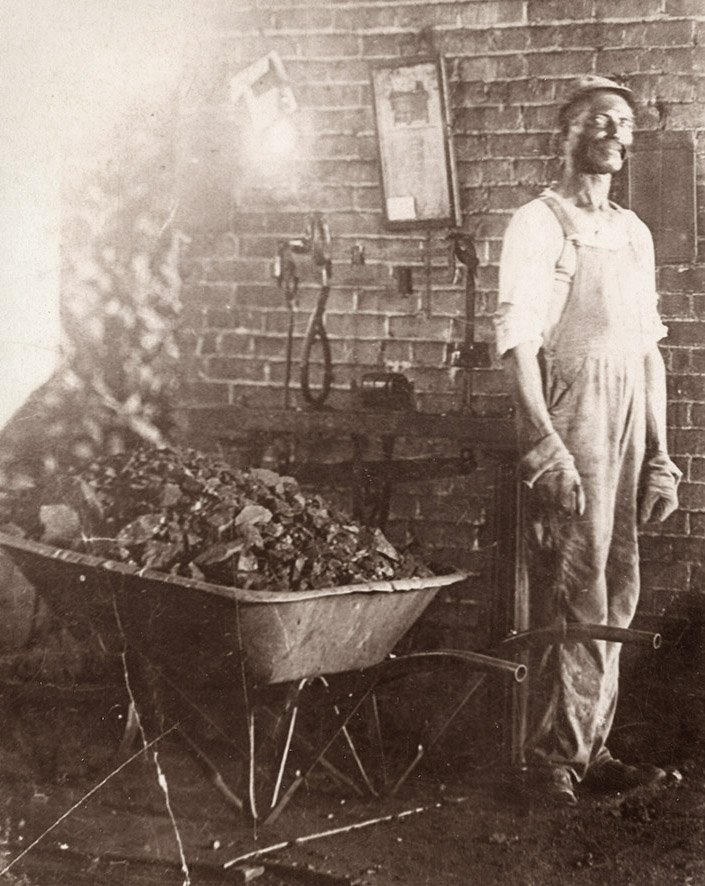

Most Clarksville residents held menial, low-wage jobs because they had little or no education. For example, they picked cotton, worked on farms, labored at the rock quarry in Round Rock, worked at the Zilker Brickyard, or held down construction jobs. Some Clarksville women worked at Woodlawn, took in laundry, or did ironing. Once the Confederate Soldiers Home opened just south of Clarksville, other residents worked there, and one resident began a community store that was located at what is now 1710 West 10th Street. Many Clarksville families augmented their income by taking in boarders. And during harvesting seasons, children left school to work with their parents in the fields.

Soon after settling in Clarksville, early residents informally organized the Sweet Home Missionary Baptist Church, which became the focal point of their lives. At first, prayer and fellowship meetings were held in the home of Edwin and Mary Smith, who were among the organizers of the church. However, by July 1882, residents were able to buy land for a church building — for $50 — and services were held under a brush arbor there. Not long after, the congregation came up with enough money to build a church building. Jacob Fontaine, who began the Gold Dollar, Austin's first Black newspaper, was its first minister.

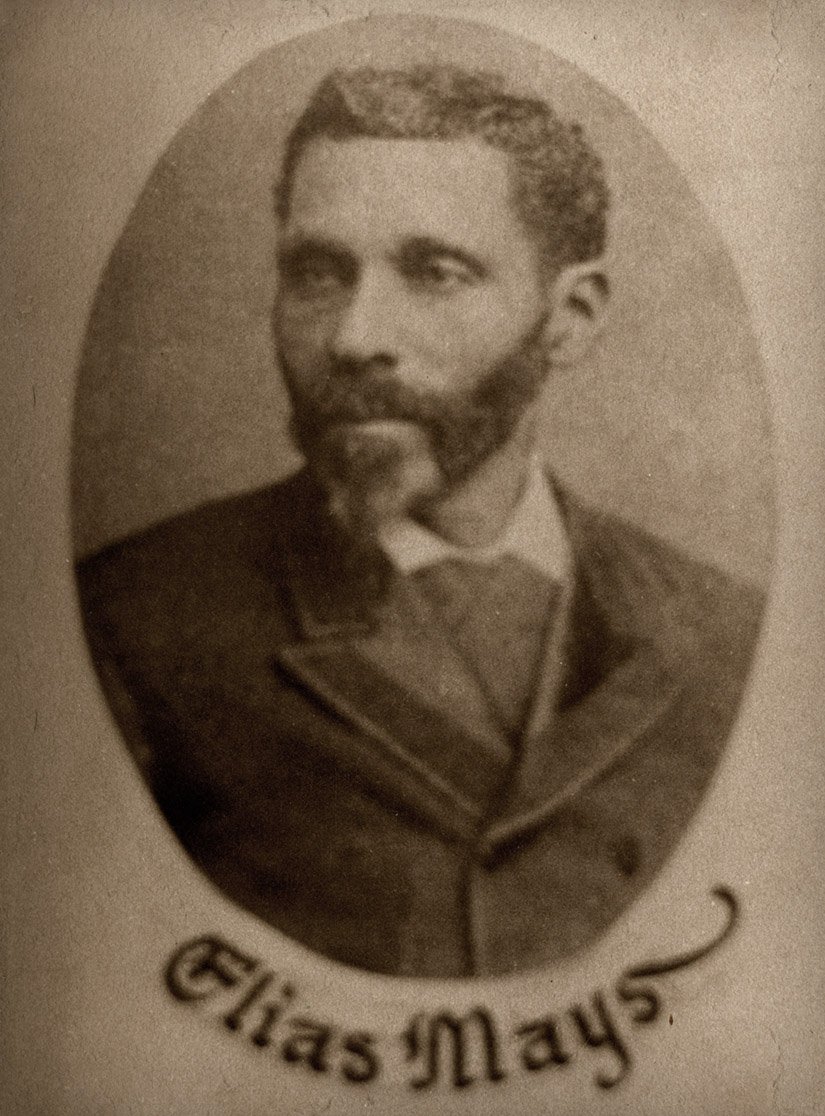

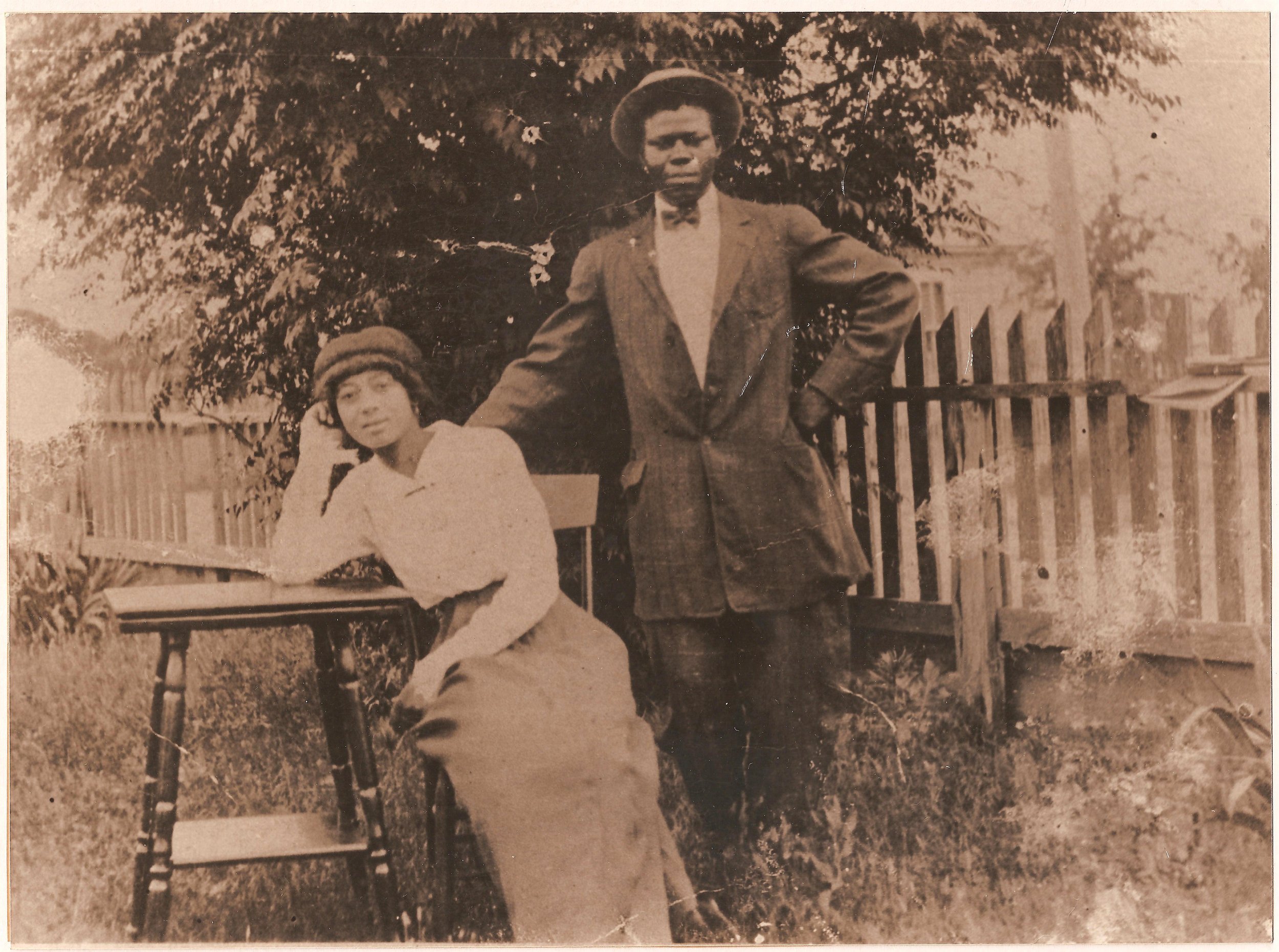

Elias Mayes (surname also spelled May and Mays), purchased two lots from Clark in 1884. Mayes served in the Texas Legislature from 1879 to 1881 and again, from 1889 to 1891. During Clarksville’s early years, Mayes’ wife Maggie taught Clarksville children in their home. Elias and Maggie were among Clarksville’s most prominent residents. Their son Ben May — the last two letters in his name were dropped at some point — later lived at 1624 West 10th. He was the first Black motion picture operator in Texas.

Eventually, rather than being educated at the Mayes’ home, Clarksville children began attending school at Sweet Home. Then in 1917, the Austin Independent School District built the Clarksville Colored School, which was located where Mary Baylor Clarksville Park is now, at 1807 West 11th Street. Initially, the one-room elementary school offered classes for 1st through 4th graders, but later it added classes for children in 5th and 6th grade. In 1965, the school was closed after the Austin public school system was fully integrated and Clarksville children were able to attend Mathews Elementary on West Lynn.